Upscaling Assays on 3D Cell Models

In a collaborative project with Nanion Technologies (https://www.nanion.de/) and the Max Reichert group at TUM hospital (https://www.med2.mri.tum.de/de/team/cv/reichert_cv.php) we investigate Printed Circuit Board (PCB) technologies for their suitability to achieve a sensor-based readout of 3D cell models such as spheroids or organoids (Projektträger Bayern, PBN-LSM-2104-0003).

One of the most beneficial features of a sensor-based, kinetic data readout is the ability to monitor the condition of 3D cell models individually and throughout the entire growth and drug incubation period. In contrast to endpoint measurements this allows additional longitudinal observations.

Multilayer PCB technology offers high-density integration of electrode structures for electric impedance recordings, industrial upscaling with low product costs and biocompatible assemblies.

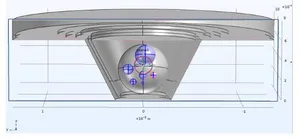

The planning of PCB design usually starts with virtual prototyping, where different kinds of electrode setups and geometries are tested as finite element models.

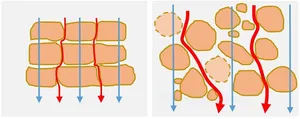

One of the challenges of measuring the electric impedance of 3D culture objects is to guide electric currents through the 3D objects of interest and to avoid bypassing of high-impedance volumes. To achieve that we use “guardring electrodes” equipotential to the measuring working electrodes.

Electric impedance measured in-vitro on 3D cellular structures in the 10 kHz frequency range will respond to changes of bulk electrical conductivity and structural changes related to alterations of cell-cell connections and cell membrane integrity or to increasing cell mass.

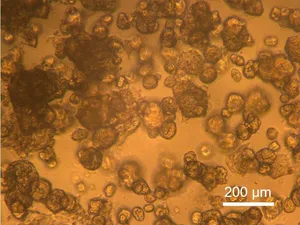

For clinical translation, the processing of small-sized patient-derived cell samples is paramount. One of the options to transform small cell samples into a screening-compatible format is the encapsulation of cells by adapting an FDA-approved workflow (http://www.austrianova.com) to a microfluidic aqueous-two-phase system.

3D cell models prepared e.g. from cancer patient-derived cells can be packaged and used as “in vitro avatars” (e.g. representing a tumor) for functional “precision oncology” assays as a part of clinical trials – with the aim to better define personalized cancer treatments. Practical screening workflows must account for aspects such as throughput, costs and diagnostic accuracy.

Contact: Dr. Martin Brischwein, brischwein@tum.de